2 min read

Special Update - Crude Oil, Refined Products & Natural Gas

We generally don't provide public "market commentary" but given the events of the past week and their impact on the energy markets, we thought we...

As energy commodity prices across the globe continue to be subject to significant volatility, we wanted to provide another look at the various energy hedging instruments and strategies available to the various participants in the energy commodity markets.

As this post will be the first of several in a series, we are going to begin by exploring how market participants can hedge their energy price risk with futures contracts, the underlying benchmarks of most of the energy hedging and price risk management strategies. In subsequent posts in the series, we'll address how energy commodity swaps, options and more complex hedging structures such as basis swaps, collars and spreads on options can be used to manage energy price risk.

In the global energy commodity markets, there are six primary energy futures contracts, four of which are traded on the CME Group’s NYMEX: WTI crude oil, Henry Hub natural gas, ultra-low sulfur diesel (ULSD) and gasoline (RBOB) and two of which are traded on ICE: Brent crude oil and gasoil. IN addition, there are hundreds of additional energy futures, swaps and options listed across the world on the likes of not only CME and ICE but numerous additional exchanges a well as over the counter (OTC) trading venues, which cover everything from biofuels to electricity to natural gas liquids.

Back to the specific focus of this post – futures contracts. In essence, a futures contract gives the buyer of the contract the right and obligation to buy the underlying commodity at the price at which he buys the futures contract. The opposite is true for the seller of a futures contract. However, in practice, very few energy futures contracts result in delivery, most are utilized for hedging and are exited, sold in the case of long positions, bought in the case of short positions, prior to expiration.

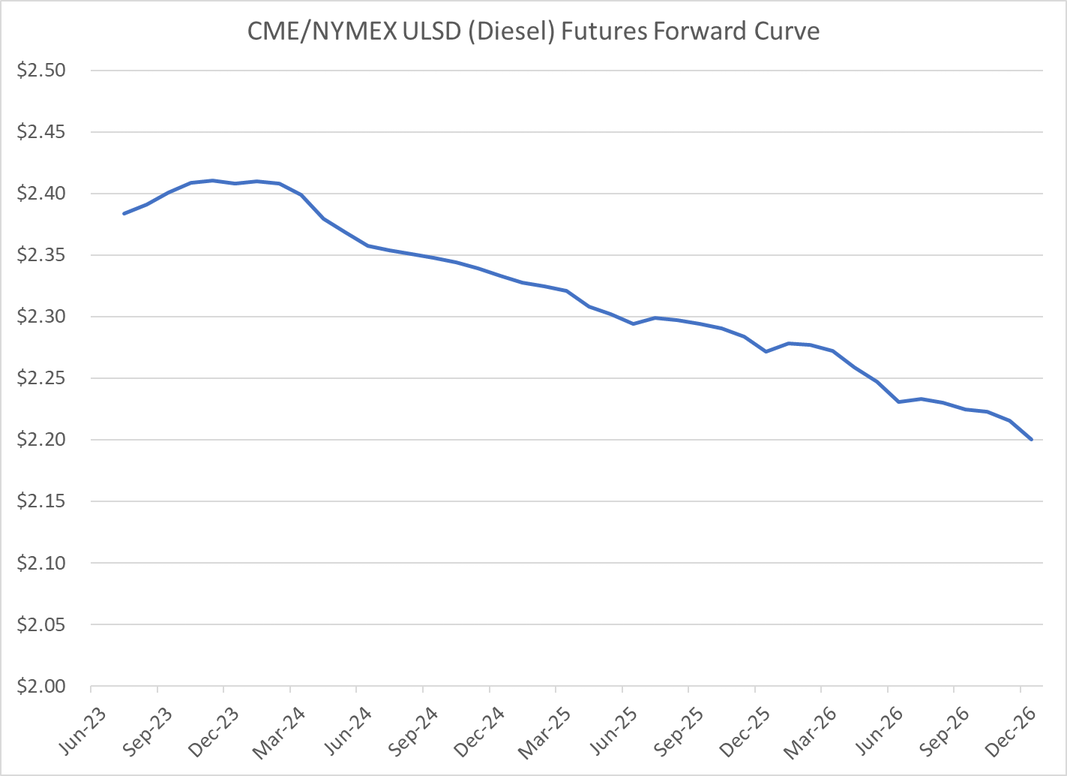

Let’s examine the case of a corporate fleet whose vehicles consume a large quantity of ultra-low sulfur diesel fuel for a specific month. For sake of simplicity, let's assume that the company is looking to hedge (by "fixing" or "locking" in the price) 42,000 gallons (1,000 BBLs) of their July consumption. To hedge their 42,000 gallons, they could buy one NYMEX ULSD futures contract. If the company had purchased an August contract based on the closing price yesterday for the August contract, they would have hedged 42,000 gallons of their August fuel consumption at a price of $2.3911/gallon.

If you are wondering why the company would purchase 42,000 gallons, the answer is that the standard ULSD contract is 42,000 gallons or 1,000 barrels. Similarly, if you are wondering why they would utilize an August, rather than a July futures contract, that is because futures contracts usually expire a month or two ahead of the actual calendar month. In the case of ULSD, the August contract expires at the end of July, hence the reason that we are assuming in this example that the company will likely choose to hedge their July fuel consumption with an August futures contract.

Let’s now assume that it is the last business day of July, the expiration date of the August ULSD futures contract. Because the company does not want to take physical delivery of the futures contract, they sell one August ULSD futures contract at the then, prevailing market price.

If the prevailing market price on the last business day of July, the price at which the company were to sell the ULSD futures contract is $3.00/gallon, the company would incur a hedging gain of $0.6089/gallon. As a result of the hedging gain, the company’s gross cost for the first 42,000 gallons of ULSD that they consume in July would be their actual cost less $0.6089/gallon hedge gain. So, if their actual cost were $4.00/gallon - assuming a base cost which is equivalent to the $3.00 futures price mentioned above as well as an additional $1.00/gallon to account for locational price differences as well as taxes, amongst other fees – their net cost would be 3.3911 thanks to the hedge gain of $0.6089.

On the other hand, if the prevailing market price on the last business day of July, the price at which the company were to sell the ULSD futures contract is $2.00/gallon, the company would incur a hedging loss of $0.3911/gallon. As a result of the hedging loss, the company’s gross cost for the first 42,000 gallons of ULSD that they consume in July would be their actual cost plus the $0.3911/gallon hedge loss. So, if their actual cost were $3.00/gallon - assuming a base cost which is equivalent to the $2.00 futures price mentioned above as well as an additional $1.00/gallon to account for locational price differences as well as taxes, amongst other fees – their net cost would be 3.3911, as they have to account for the actual cost plus the hedging loss of $0.3911.

As an aside, if held to expiration, the seller (short) of a futures contract is obligated to make delivery of the commodity while the buyer (long) of a futures contract is required to take delivery of (receive) the commodity.

This same and/or a similar methodology could also be utilized by consumers and end-users who need to hedge other energy commodities – everything from biofuels to electricity to natural gas liquids such as propane. Likewise, similar but opposite methodologies are often used by energy producers – such as E&P companies as well as refiners – whose revenues and profit margins are heavily exposed to volatile energy commodity prices as well.

While there are a quite a few details that need to be considered before a company buys or sells futures contracts to hedge their energy commodity price risk, the methodology is pretty straightforward: If you need to hedge your exposure against potentially higher energy prices you can do so by buying an energy futures contact, if you need to hedge your exposure to declining energy prices you can do so by selling an futures contract.

This post is the first in an introductory series on energy hedging. The subsequent four posts can be found via the following links:

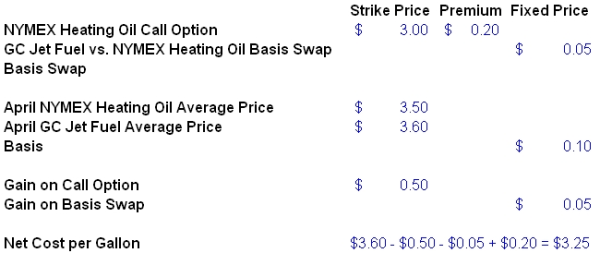

Energy Hedging 101 - Basis Swaps

If you would like to discuss how we can potentially help you to hedge your organization's energy price risk, please feel free to contact us.

2 min read

We generally don't provide public "market commentary" but given the events of the past week and their impact on the energy markets, we thought we...

3 min read

This post is the fourth, in an ongoing series, covering the basics of energy hedging. The first three posts in the series explored energy hedging...

2 min read

As the debates and hearings regarding the implementation of Dodd-Frank continue in Washington, we wanted to pass along a few updates, especially as...