3 min read

Hedging Refining Profit Margins with Crack Spread Options

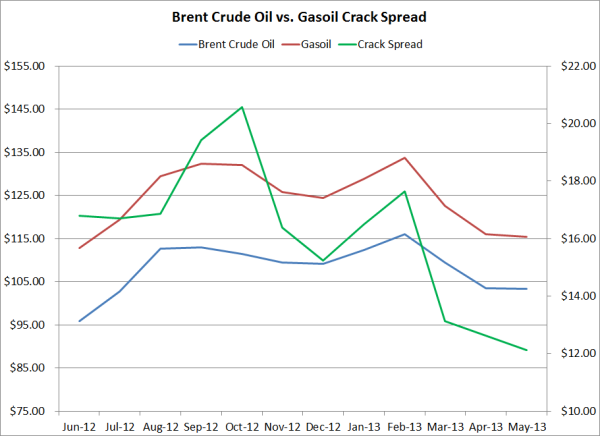

Over the past year, refining profit margins have been quite volatile. As an example, Brent crude oil/gasoil calendar swap crack spreads have traded...

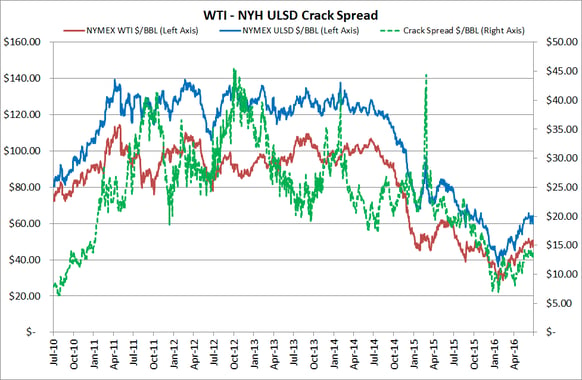

Over the course of the past year, refining profit margins have been all over the map. As an example, over the course of the past year, the WTI-NY Harbor ultra-low sulfur diesel (ULSD) crack spread has traded as high as $22.92/BBL and as low as $6.89/BBL while averaging $14.03/BBL. Crack spreads on other crude oils (Brent, Light Louisiana Sweet, etc.) and various refined products (diesel, gasoline, jet fuel, etc.) have been similarly volatile.

A basic crack spread is the 1:1 crack spread which represents the refining profit margin, that is buying crude oil and selling the refined products (i.e. diesel fuel, gasoline, jet fuel), thereby locking in the difference between the refined products and crude oil. While crack spread are quoted in dollars per barrel and many refined products are quotes in dollars per metric ton or dollars per gallons, if the refined product is not quoted in dollars per barrel it needs to be converted to dollars per barrel. For example, to convert NY Harbor ULSD we multiply the dollar per gallon price of ULSD by 42 as there are 42 gallons in a barrel. If the refined product value is higher than the price of the crude oil, the crack spread is profitable. On the other hand, if the refined product value is less than the value of crude oil, then the crack spread is not profitable.

Just as oil producers and consumers have the ability to hedge their exposure to volatile petroleum prices, refiners have the ability to hedge their exposure as well. In fact, one could argue that refiners face an even greater need to hedge than producers and consumers as their profit margins are based on the price of not one commodity, but at least two and often several: the price of their input (crude oil) as well as their outputs (bunker fuel, heating oil, gasoline, diesel fuel, gasoil, jet fuel, etc.). In order to mitigate their exposure to crack spread price volatility, many refiners hedge the crack spread by purchasing crude oil futures or swaps and simultaneously selling refined products futures or swaps as the results allows the refiner to lock-in or fix the refining margin.

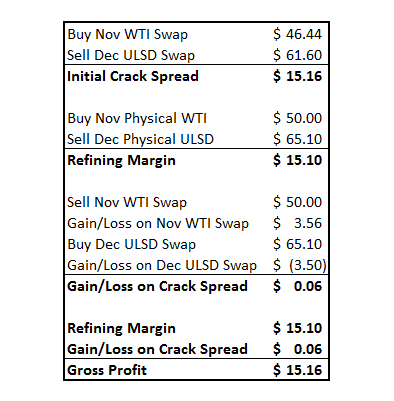

As an example, let's assume that a refiner is interested in hedging their December ULSD refining margin as they are content with the current cracks spread available in the market as it is higher than the $12.50 crack spread in their annual budget. Based on the close of business Friday, the December WTI-ULSD crack spread is currently trading at $15.16/BBL based on the December ULSD swap trading at $61.60/BBL ($1.4666/gallon) and the November WTI swap trading at $46.44/BBL. The refiner is buying November crude oil and selling December ULSD as refiners generally purchase crude oil for processing in a given month, and subsequently refine and sell the refined products during the following month.

Scenario I: Crude Oil @ $50.00/BBL and ULSD @ $65.10/BBL

Let’s assume that during the month of November that the prompt NYMEX WTI futures contract (which determines the settlement price of the refiner’s WTI swap) is trading higher and averages $50.00/BBL. As a result, the refiner incurs a gain of $3.56/BBL on the long crude oil swap. In addition, because the WTI cash (physical) market and the WTI futures market are highly correlated, the refiner purchases physical crude oil in the cash market for $50/BBL as well.

Let’s also assume that during the month of December that the prompt NYMEX ULSD futures contract is trading higher (which determines the settlement price of the refiner’s ULSD swap) and averages $65.10/BBL ($1.55/gallon). As a result, the refiner incurs a loss of $3.50/BBL ($0.08/gallon) on the short ULSD swap. However, similar to the crude oil cash (physical) market, the ULSD cash market and the ULSD futures market also have a strong correlation, leading the refiner to sell their ULSD production in the cash market for $1.55/gallon ($65.10/BBL).

As a result of all of the above, in this scenario the refiner generates a refining margin of $15.10/BBL ($0.36/gallon) while incurring a net hedging gain of $0.06/BBL ($3.56/BBL gain on the crude oil swap and $3.50/BBL loss on the ULSD swap), the combination resulting in a gross profit of $15.16/BBL.

In this scenario if the refiner had not hedged the crack spread, their gross profit would have been $15.10/BBL, rather than $15.16/BBL as a result of the hedge.

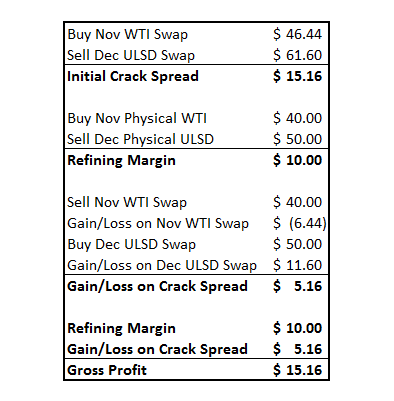

Scenario II: Crude Oil @ $40.00/BBL and ULSD @ $50.00/BBL

Let’s assume that during the month of November that the prompt NYMEX WTI futures contract is trading lower and averages $40.00/BBL. In this case, the refiner incurs a loss of $6.44/BBL on the long crude oil swap. As is the case in the first scenario, the refiner purchases physical crude oil in the cash market for the same price as the WTI swap, $40/BBL.

Let’s also assume that during the month of December that the prompt NYMEX ULSD futures contract is trading lower and averages $50.00/BBL ($1.19/gallon). As a result, the refiner incurs a gain of $11.60/BBL ($0.28/gallon) on the short ULSD swap. The refiner also sells their ULSD production in the cash market for the same as the ULSD swap, $1.19/gallon ($50/BBL).

In the second scenario the refiner generates a refining margin of $10.00/BBL ($0.24/gallon), incurs a net gain of $5.16/BBL on the swaps ($6.44/BBL loss on the WTI swap and $11.60/BBL gain on the ULSD swap), the combination again resulting in a gross profit of $15.16/BBL.

In this scenario if the refiner had not hedged the crack spread, their gross profit would have only been $10.00/BBL, $5.16/BBL less than they received as a result of the hedge.

While these examples highlight hedging WTI-ULSD crack spreads, the same methodology can be applied to hedge refining margins involving both other crude oils (Brent, LLS, etc.) as well as other refined products (bunker fuel, gasoline, jet fuel, gasoil, etc.).

3 min read

Over the past year, refining profit margins have been quite volatile. As an example, Brent crude oil/gasoil calendar swap crack spreads have traded...

2 min read

Last April, in a post titled The Ultimate Airline Fuel Hedge: Buy A Refinery, we highlighted Delta Airlines acquisition of the Trainer refinery from...

1 min read

As has been well reported elsewhere, Delta Airlines is rumored to be in negotiations to buy ConocoPhillips' Trainer, Pennsylvania refinery in order...