3 min read

The Layman's Guide to Gasoil Hedging with Futures

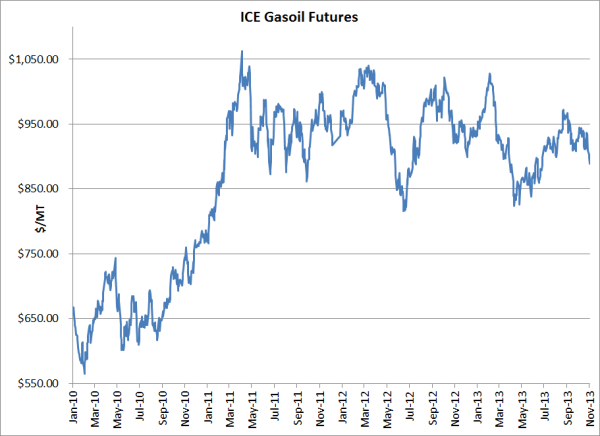

As many companies are beginning to plan for 2014, we have received quite a few inquiries from companies who are looking into hedging their gasoil...

3 min read

Mercatus Energy : Sep 7,2011

While many consumers and politicians are hopeful that "anti-speculation" regulations (e.g. Dodd-Frank) will ultimately lead to lower gasoline prices at the pump, such hope will most likely lead to another disappointment in Washington and across the country. And the reason is one that will surprise most whom are not familiar with the global oil markets.

While U.S. retail gasoline prices are thought to be driven by West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil prices, the reality is that Brent crude oil is the real driver of U.S gasoline prices. While this seems counter-intuitive to those not familiar with the global oil markets, the reasoning is actually quite simple.

The NYMEX crude oil contract (WTI) is deliverable in Cushing, Oklahoma, which is a landlocked market with few, commercial, interconnects to the international markets. On the contrary, the delivery point of the NYMEX RBOB gasoline contract is New York Harbor, which provides waterborne access to the international markets. The combination of these two factors means that the RBOB gasoline contract is, usually, representative of the cost of delivering foreign refined gasoline to the East Coast and/or the cost of not exporting U.S. refined gasoline to international markets. As such, Brent (the international crude oil benchmark) and other international, waterborne crude oils are currently the primer driver of U.S. gasoline prices, not WTI.

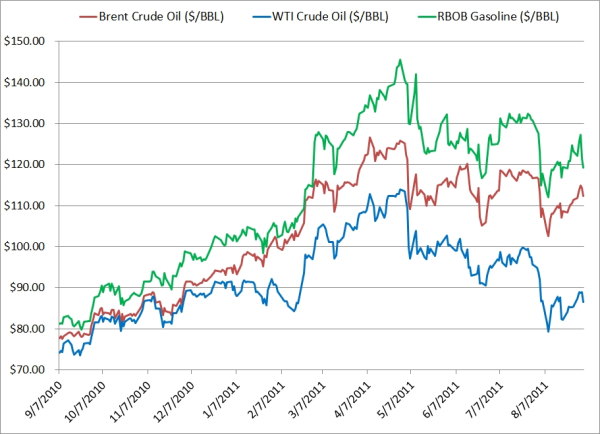

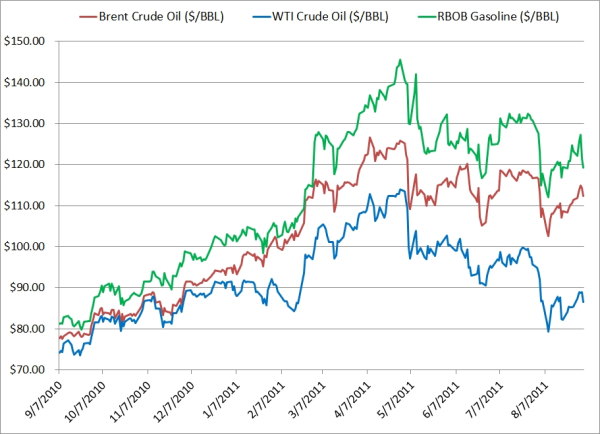

The following chart shows ICE Brent, NYMEX WTI and NYMEX RBOB (RBOB has been converted from gallons to barrels: 42 gallons = 1 barrel) prompt month futures over the past year.

According to data from Energy Information Administration, the cost for domestic refiners to acquire crude oil in June were as follows:

East Coast: $104.26/BBL

Midwest: $97.77/BBL

Gulf Coast: $105.75/BBL

Rocky Mountains: $90.28/BBL

West Coast: $105.85/BBL

On the contrary, the prices at which U.S. refiners sold gasoline to resellers (retailers) in June were as follows:

East Coast: $2.973/Gallon ($124.87/BBL)

Midwest: $2.968/Gallon ($124.66/BBL)

Gulf Coast: $2.914/Gallon ($122.39/BBL)

Rocky Mountains: $2.98/Gallon ($125.16/BBL)

West Coast: $3.033 (127.39/BBL)

As the data shows, the availability of "cheap" crude oil in the Midwest and Rockies didn't lead to lower gasoline prices, it simply allowed refiners in those regions to capture better profit margins (crack spreads), which shouldn't come as a surprise. To emphasize this point, the following is from ConocoPhillips' quarterly report for the second quarter of 2011 (ended June 30, 2011):

Domestic refining margins significantly improved in the second quarter of 2011, while international refining margins decreased slightly. The U.S. 3:2:1 crack spread, which is primarily WTI-based, increased 107 percent in the second quarter of 2011, compared with the second quarter of 2010, and 33 percent compared with the first quarter of 2011. In the second quarter of 2011, these increases were a result of stronger demand for higher-priced light crudes and increased crude supplies in the Midcontinent area, causing WTI to trade at a discount relative to waterborne crudes. Refineries capable of processing WTI and crude oils that are WTI-based are benefiting from the lower crude oil prices.

Basic economics dictates that commodity prices are set "at the margin," which in this scenario, simply means that retail gasoline prices aren't being driven by the lowest cost crude oil available for domestic refining, but by the most expensive barrels, which are currently barrels priced on Brent, not WTI.

Adding salt to the wound is the current state of global economic environment. For starters, the U.S. dollar is weak, and because oil is priced in U.S. dollars, those purchasing oil with stronger currencies are able to buy the same barrel for less. In addition, while the U.S. economy is stagnant or worse, significant economic growth is still occurring in much of Asia and South America. And economic growth requires oil. As a result, the current demand for Brent priced crude is higher than that of WTI priced crude. As numerous others have noted (see Craig Pirrong's excellent post titled, A Tale of Two Contracts), in due time, as the North American crude oil transportation capacity is expanded (which will allow Midcontinent and Canadian barrels to be delivered to the Gulf Coast), the spread between Brent and WTI should narrow.

The Brent crude oil market certainly isn't a perfect market, it has numerous problems which are beyond the scope of this post but, for the time being Brent crude oil prices are driving U.S. gasoline prices and there is little that American politicians and regulators can do to change this fact.

3 min read

As many companies are beginning to plan for 2014, we have received quite a few inquiries from companies who are looking into hedging their gasoil...

3 min read

As energy trading and risk management advisors, we regularly receive inquiries regarding if, when and how a company might hedge their exposure to...

3 min read

As we're often asked to help companies develop de novo fuel hedging initiatives, we thought we would highlight the primary building blocks of a fuel...